Real Time Signal Processing in Python

Wouldn't it be nice if you could do real time audio processing in a convenient programming language? Matlab comes to mind as a convenient language for signal processing. But while Matlab is pretty fast, it is really only fast for algorithms that can be vectorized. In audio however, we have many algorithms that need knowledge about the previous sample to calculate the next one, so they can't be vectorized.

But this is not going to be about Matlab. This is going to be about Python. Combine Python with Numpy (and Scipy and Matplotlib) and you have a signal processing system very comparable to Matlab. Additionally, you can do real-time audio input/output using PyAudio. PyAudio is a wrapper around PortAudio and provides cross platform audio recording/playback in a nice, pythonic way. (Real time capabilities were added in 0.2.6 with the help of yours truly).

However, this does not solve the problem with vectorization. Just like Matlab, Python/Numpy is only fast for vectorizable algorithms. So as an example, let's define an iterative algorithm that is not vectorizable:

A Simple Limiter

A limiter is an audio effect that controls the system gain so that it does not exceed a certain threshold level. One could do this by simply cutting off any signal peaks above that level, but that sounds awful. So instead, the whole system gain is reduced smoothly if the signal gets too loud and is amplified back to its original gain again when it does not exceed the threshold any more. The important part is that the gain change is done smoothly, since otherwise it would introduce a lot of distortion.

If a signal peak is detected, the limiter will thus need a certain amount of time to reduce the gain accordingly. If you still want to prevent all peaks, the limiter will have to know of the peaks in advance, which is of course impossible in a real time system. Instead, the signal is delayed by a short time to give the limiter time to adjust the system gain before the peak is actually played. To keep this delay as short as possible, this "attack" phase where the gain is decreased should be very short, too. "Releasing" the gain back up to its original value can be done more slowly, thus introducing less distortion.

With that out of the way, let me present you a simple implementation of such a limiter. First, lets define a signal envelope \(e[n]\) that catches all the peaks and smoothly decays after them:

\[ e[n] = \max( |s[n]|, e[n-1] \cdot f_r ) \]

where \(s[n]\) is the current signal and \(0 < f_r < 1\) is a release factor.

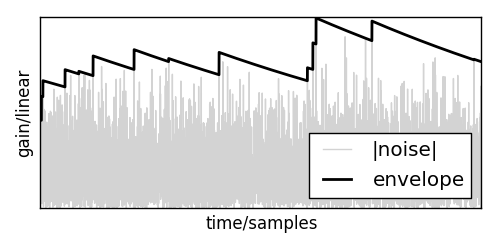

If this is applied to a signal, it will create an envelope like this:

Based on that envelope, and assuming that the signal ranges from -1 to 1, the target gain \(g_t[n]\) can be calculated using

\begin{equation} g_t[n] = \begin{cases} 1 & e[n] < t \\\\ 1 + t - e[n] & e[n] > t \end{cases} \end{equation}Now, the output gain \(g[n]\) can smoothly move towards that target gain using

\[ g[n] = g[n-1] \cdot f_a + g_t[n] \cdot (1-f_a) \]

where \(0 < f_a \ll f_r\) is the attack factor.

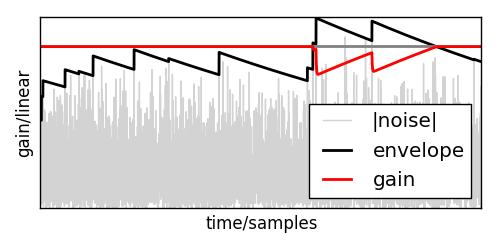

Here you can see how that would look in practice:

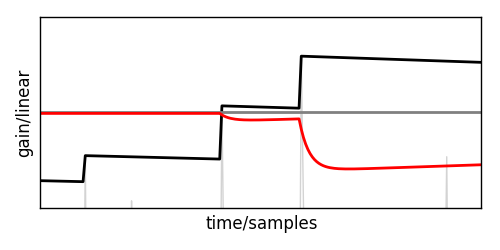

Zooming in on one of the limited section reveals that the gain is actually moving smoothly.

This gain can now be multiplied on the delayed input signal and will safely keep that below the threshold.

In Python, this might look like this:

class Limiter: def __init__(self, attack_coeff, release_coeff, delay, dtype=float32): self.delay_index = 0 self.envelope = 0 self.gain = 1 self.delay = delay self.delay_line = zeros(delay, dtype=dtype) self.release_coeff = release_coeff self.attack_coeff = attack_coeff def limit(self, signal, threshold): for i in arange(len(signal)): self.delay_line[self.delay_index] = signal[i] self.delay_index = (self.delay_index + 1) % self.delay # calculate an envelope of the signal self.envelope *= self.release_coeff self.envelope = max(abs(signal[i]), self.envelope) # have self.gain go towards a desired limiter gain if self.envelope > threshold: target_gain = (1+threshold-self.envelope) else: target_gain = 1.0 self.gain = ( self.gain*self.attack_coeff + target_gain*(1-self.attack_coeff) ) # limit the delayed signal signal[i] = self.delay_line[self.delay_index] * self.gain

Note that this limiter does not actually clip all peaks completely, since the envelope for a single peak will have decayed a bit before the target gain will have reached it. Thus, the output gain will actually be slightly higher than what would be necessary to limit the output to the threshold. Since the attack factor is supposed to be significantly smaller than the release factor, this does not matter much though.

Also, it would probably be more useful to define the factors \(f_a\) and \(f_r\) in terms of the time they take to reach their target and the threshold \(t\) in dB FS.

Implementing audio processing in Python

A real-time audio processing framework using PyAudio would look like this:

(callback is a function that will be defined shortly)

from pyaudio import PyAudio, paFloat32 pa = PyAudio() stream = pa.open(format = paFloat32, channels = 1, rate = 44100, output = True, frames_per_buffer = 1024, stream_callback = callback) while stream.is_active(): sleep(0.1) stream.close() pa.terminate()

This will open a stream, which is a PyAudio construct that manages input and output to/from one sound device. In this case, it is configured to use float values, only open one channel, play audio at a sample rate of 44100 Hz, have that one channel be output only and call the function callback every 1024 samples.

Since the callback will be executed on a different thread, control flow will continue immediately after pa.open(). In order to analyze the resulting signal, the while stream.is_active() loop waits until the signal has been processed completely.

Every time the callback is called, it will have to return 1024 samples of audio data. Using the class Limiter above, a sample counter counter and an audio signal signal, this can be implemented like this:

limiter = Limiter(attack_coeff, release_coeff, delay, dtype) def callback(in_data, frame_count, time_info, flag): if flag: print("Playback Error: %i" % flag) played_frames = counter counter += frame_count limiter.limit(signal[played_frames:counter], threshold) return signal[played_frames:counter], paContinue

The paContinue at the end is a flag signifying that the audio processing is not done yet and the callback wants to be called again. Returning paComplete or an insufficient number of samples instead would stop audio processing after the current block and thus invalidate stream.is_active() and resume control flow in the snippet above.

Now this will run the limiter and play back the result. Sadly however, Python is just a bit too slow to make this work reliably. Even with a long block size of 1024 samples, this will result in occasional hickups and discontinuities. (Which the callback will display in the print(...) statement).

Speeding up execution using Cython

The limiter defined above could be rewritten in C like this:

// this corresponds to the Python Limiter class. typedef struct limiter_state_t { int delay_index; int delay_length; float envelope; float current_gain; float attack_coeff; float release_coeff; } limiter_state; #define MAX(x,y) ((x)>(y)?(x):(y)) // this corresponds to the Python __init__ function. limiter_state init_limiter(float attack_coeff, float release_coeff, int delay_len) { limiter_state state; state.attack_coeff = attack_coeff; state.release_coeff = release_coeff; state.delay_index = 0; state.envelope = 0; state.current_gain = 1; state.delay_length = delay_len; return state; } void limit(float *signal, int block_length, float threshold, float *delay_line, limiter_state *state) { for(int i=0; i<block_length; i++) { delay_line[state->delay_index] = signal[i]; state->delay_index = (state->delay_index + 1) % state->delay_length; // calculate an envelope of the signal state->envelope *= state->release_coeff; state->envelope = MAX(fabs(signal[i]), state->envelope); // have current_gain go towards a desired limiter target_gain float target_gain; if (state->envelope > threshold) target_gain = (1+threshold-state->envelope); else target_gain = 1.0; state->current_gain = state->current_gain*state->attack_coeff + target_gain*(1-state->attack_coeff); // limit the delayed signal signal[i] = delay_line[state->delay_index] * state->current_gain; } }

In contrast to the Python version, the delay line will be passed to the limit function. This is advantageous because now all audio buffers can be managed by Python instead of manually allocating and deallocating them in C.

Now in order to plug this code into Python I will use Cython. First of all, a "Cython header" file has to be created that declares all exported types and functions to Cython:

cdef extern from "limiter.h": ctypedef struct limiter_state: int delay_index int delay_length float envelope float current_gain float attack_coeff float release_coeff limiter_state init_limiter(float attack_factor, float release_factor, int delay_len) void limit(float *signal, int block_length, float threshold, float *delay_line, limiter_state *state)

This is very similar to the C header file of the limiter:

typedef struct limiter_state_t { int delay_index; int delay_length; float envelope; float current_gain; float attack_coeff; float release_coeff; } limiter_state; limiter_state init_limiter(float attack_factor, float release_factor, int delay_len); void limit(float *signal, int block_length, float threshold, float *delay_line, limiter_state *state);

With that squared away, the C functions are accessible for Cython. Now, we only need a small Python wrapper around this code so it becomes usable from Python:

import numpy as np cimport numpy as np cimport limiter DTYPE = np.float32 ctypedef np.float32_t DTYPE_t cdef class Limiter: cdef limiter.limiter_state state cdef np.ndarray delay_line def __init__(self, float attack_coeff, float release_coeff, int delay_length): self.state = limiter.init_limiter(attack_coeff, release_coeff, delay_length) self.delay_line = np.zeros(delay_length, dtype=DTYPE) def limit(self, np.ndarray[DTYPE_t,ndim=1] signal, float threshold): limiter.limit(<float*>np.PyArray_DATA(signal), <int>len(signal), threshold, <float*>np.PyArray_DATA(self.delay_line), <limiter.limiter_state*>&self.state)

The first two lines set this file up to access Numpy arrays both from the Python domain and the C domain, thus bridging the gap. The cimport limiter imports the C functions and types from above. The DTYPE stuff is advertising the Numpy float32 type to C.

The class is defined using cdef as a C data structure for speed. Also, Cython would naturally translate every C struct into a Python dict and vice versa, but we need to pass the struct to limit and have limit modify it. Thus, cdef limiter.limiter_state state makes Cython treat it as a C struct only. Finally, the np.PyArray_DATA() expressions expose the C arrays underlying the Numpy vectors. This is really handy since we don't have to copy any data around in order to modify the vectors from C.

As can be seen, the Cython implementation behaves nearly identically to the initial Python implementation (except for passing the dtype to the constructor) and can be used as a plug-in replacement (with the aforementioned caveat).

Finally, we need to build the whole contraption. The easiest way to do this is to use a setup file like this:

from distutils.core import setup from distutils.extension import Extension from Cython.Distutils import build_ext from numpy import get_include ext_modules = [Extension("cython_limiter", sources=["cython_limiter.pyx", "limiter.c"], include_dirs=['.', get_include()])] setup( name = "cython_limiter", cmdclass = {'build_ext': build_ext}, ext_modules = ext_modules )

With that saved as setup.py, python setup.py build_ext --inplace will convert the Cython code to C, and then compile both the converted Cython code and C code into a binary Python module.

Conclusion

In this article, I developed a simple limiter and how to implement it in both C and Python. Then, I showed how to use the C implementation from Python. Where the Python implementation is struggling to keep a steady frame rate going even at large block sizes, the Cython version runs smoothly down to 2-4 samples per block on a 2 Ghz Core i7. Thus, real-time audio processing is clearly feasable using Python, Cython, Numpy and PyAudio.

You can find all the source code in this article at https://github.com/bastibe/simple-cython-limiter

Disclaimer

- I invented this limiter myself. I could invent a better sounding limiter, but this article is more about how to combine Python, Numpy, PyAudio and Cython for real-time signal processing than about limiter design.

- I recently worked on something similar at my day job. They agreed that I could write about it so long as I don't divulge any company secrets. This limiter is not a descendant of any code I worked on.

- Whoever wants to use any piece of code here, feel free to do so. I am hereby placing it in the public domain. Feel free to contact me if you have questions.